What is left of September 11? Nothing and everything. Fifteen years ago, literally overnight, the world entered a new era. In one of those rare moments in history where the observer can subsequently clearly see a ‘before’ and an ‘after’, the global context of all things – social, political, cultural, and geostrategic – was profoundly altered. Few aspects of our lives, if any at all, as well as the way we relate to each other, remained unaffected by the attacks on the United States and their multifaceted aftermath. The inception of unceasing global wars, the reinvigoration of armed groups of all hues, the launching of all-encompassing international security policies, the overhaul of entire bureaucracies now expanding their tentacles into all societal fields, and increased antipathy between cultural and religious communities – all of this, and much more, came to pass in rapid succession objectively defining the parameters of the new reality of the early twenty-first century.

Is there, we could nonetheless ask, overemphasis of the so-called ‘impact of 9/11’ talk? Have we not exaggerated the importance of a single terrorist incident (whatever its magnitude) when such attacks had long taken place earlier everywhere and have continued since with widespread lethality and tragedy? In fairness, no. However easy overstatement is these days and particularly so as it relates to terrorism, there is objectively no overstating the indelible imprint that the events of the autumn of 2001 left on the world. Quantitatively, the mightiest country in the world (at a time, too, when that nation was at the height of its post-Cold War unipolar moment) was attacked at the heart of its economic and defense infrastructure, by what was then the strongest armed group and in what represented the largest mass casualty terrorist operation in contemporary history. Qualitatively, 9/11 led to a series of changes that impacted not merely the United States but the larger world. Other events changed the life of a nation. Earlier, series of events within a larger tract of time (colonialism, industrialization, world wars…) transformed regions gradually. Seldom, however, did a single, (two-hour) event lead so rapidly to visible changes in the furthest recesses of the world.

And yet, today, fifteen years later, ‘9/11’ seems most paradoxically a fainted memory, and reference to it, except during its anniversary, has markedly decreased in politics, social debate, education, and across the arts. A new generation – the ‘9/11 generation’ we could term it, as it were – is growing up with but a notional understanding of what the events were about, what reality preceded them, and what environment came after. The event maintains maximal gravitas, even sacralization, but one that is nonetheless couched in a measure of vagueness. The distinct feeling that ‘the world is changed’ vividly felt in that Lord-of-the-Rings-ominous-opening-lines mode spoken by Galadriel has dissipated; 9/11 is absent and yet so present in that most uneasy of ways. The shell-shocked, weary-eyed numbed-out New Yorker – “Was it the fire downtown?” sang Steely Dan later on in their poetic post-9/11 inquiry as to what happened to the insouciant Mona they knew and who was now shutting herself down hovering above Manhattan in her high-rise apartment – have processed this and moved on. The routinization of 9/11 partakes, however, of a wider experience than purely the American one.

If 9/11 seems absent, it is in reality because it is so centrally present in the new world we inhabit and which it has come to define with such authority. Its ubiquity is systemic and thus invisible. We see it in everything around us but three dimensions dominate. Firstly, once merely a feature of international security, terrorism now occupies a central place in global affairs. The issue itself comes readily and naturally to most citizens around the world as amongst the key issues they are occupied and preoccupied with. As such, however, the discussion on terrorism has lost something essential by virtue of being boxed in contours that demarcate it solely on the basis of political considerations, security concerns, and intellectual taboos. Secondly, as a result of such elevation, international affairs have been increasingly accommodating a de facto militarization that has importantly sidelined diplomacy. Reference to the ‘Global War on Terror’ might have diminished but that disposition remains in full swing, from Washington to Islamabad by way of Brussels and Ankara – a phasing out that betrays a redundancy and an acceptance of that ‘war’ more than anything else. Finally, the ghost of 9/11 is present daily as the changes it introduced are carried forward by way of a redefined relationship between citizen and state. Invocation of the ‘T’ word, identification of the threat of radical Islamism, and declamatory statements on the urgency of any related measure suffice nowadays to demand compliance from a citizenry (driving Humvees and playing with private drones), that gradually forgets that it is the ultimate seat of such decisions. The irony of mythologized memory, however, is that neither the forgetting nor its sacralization necessarily settle the original issues.

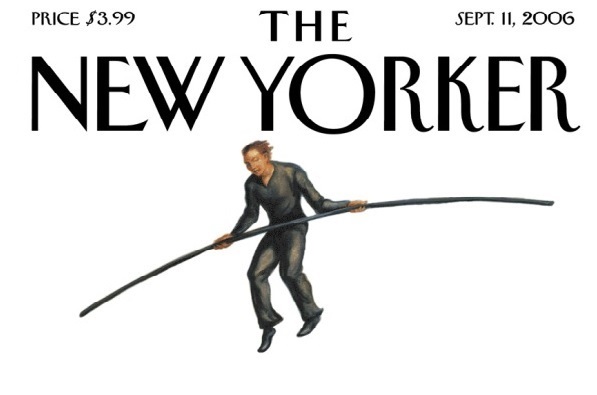

Illustration: “Soaring Spirit” by John Mavroudis and Owen Smith © The New Yorker Magazine, September 11, 2006.