In France, where you can no longer totally be ‘a free man’ (the country is under open-ended state of emergency since November 2015), contrary to what Joni Mitchell nonchalantly sang long ago –although you can still (nervously) ‘kiss on main street’, as the late folk poetess had also vocalized – the contemporary transnationalization of political violence is, according to local media, summed-up in the straightforward opposition between two local intellectual schools of thought. That will conveniently do it. In this corner, an argument about ‘the Islamization of radicalism’, and, on the other side, an alternative view on ‘the radicalization of Islam’. Pick your favorite (or disliked), fit the facts (or rationalize them), draft a policy (ever so quickly), and move on to relate any new development (however dissonant) to it.

Leave it indeed to Parisians and their time-honored tradition in that regard to turn a distant, complex, and international set of questions, with all manners of ramifications, into a Balzacesque affair featuring posture. Faced with an increase of attacks on their soil in 2015, French state and society have thus massively invested the question of the current transnational violence pursued in recent years by both armed groups such as Al Qaeda or the Islamic State and individual operators such as Anders Breivik or the Tsarnaev brothers. Having dutifully ticked the twin, self-serving and eminently misleading boxes of ‘they attack us because of who we are’ and ‘we will not cave in in the face of totalitarian ideologies’, the discussion moved on to try to identify an explanation that could be built into some sort of consensus. In post-9/11 United States, that was ruthlessly dealt with immediately by moving everything and everyone into ‘Global War on Terror’ territory. Such efficiency is not Gallic, and debate and strikes must here necessarily ensue.

Dichotomization, simplicity, and staging

Beyond its media-fueled theatrics, the current Islamization of radicalism vs. the radicalization of Islam fracas is revealing three key dystrophies of our era: the dichotomization of all things, the search for a single response in the face of complexity, and the constant and sterile staging of thought. From CNN’s 1990s Crossfire to RT’s Crosstalk in the 2010s, by way of Al Jazeera’s Al Itijah al Mu’akiss in the 2000s, reductionism of current affairs to essentialized viewpoints has become a most problematic trademark of our times. As a result of such socialization-in-the-making, both policy-makers and students increasingly approach international affairs with an impatience for history and multilayered sequences. Instead, they readily search ‘quick fixes’, ‘overarching concepts’, ‘lead factors’, ‘so-what’s-the-answers’, and ‘bottom lines’.

Shortcuts of this type can hardly provide helpful – much less valid – responses to the arresting mutation of violence in the late twentieth/early twenty-first century. Islamization of radicalism or radicalization of Islam? Would that it were so. What is engulfing France is much more complex and in fact underwritten by at least the following: the unsettled colonial history of France catching up with it, the evolving nature of post-colonialism itself, the legacy of Al Qaeda’s global martiality, the post-modernity of ISIS, the nascent hybridity of ‘AQISIS’ patterns, France’s military interventionism, its economic crisis, and its poor political leadership. Religion into violence or violence into religion? Really? To understand 9/11, the fall of Mosul, or the Kouachi Brothers? Not so much, nothing new, and at best providing only partial answers.

More importantly, the construction of this false debate is also characterized by the active disappearance of the global south intellectual on a set of issues that are eminently arresting for him or her. An astute New Yorker-Londoner observer of the Middle East recently asked me whether the thinkers associated with these different schools had, in that regard, a responsibility in bringing the debate to this cusp and closing the space in such a way. Certainly, the interrogation is valid and intellectual hegemony (as opposed to gamesmanship) too often finds its way in this scene. Ultimately, however, it is not the individuals themselves but the representation of their ideas by lazy media and political actors that is problematic.

Finally, truth be told, self-centeredness is not exclusive to the French. A recent Frontline documentary rehearsed extensively the familiar ‘we created ISIS’ line – used in the United States by academia, media, and policy-making to circumvent proper analysis of the self-sustaining agency behind the groups (see earlier, ‘we created Al Qaeda’). And similarly, the countries of the Middle East bask, for their part, in the bliss of ignoring the deeper drivers of the mess in their midst. A chaos they so complacently accompanied fatalistically and whose magical conceptualizing they can now also import, at their intellectual peril.

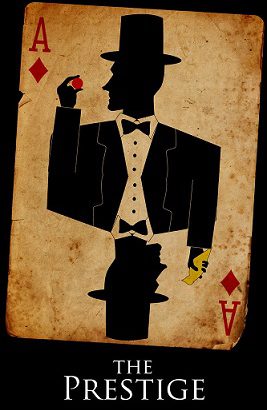

Illustration: The Prestige, 2006 © Deviant Art, WillaTree 7.