The Russian playwright Anton Chekov wrote in 1889 that if, in the first act of a play, a pistol is hung on the wall, then it will be fired by the third act. Inevitably coming into play, since it was passively promised, such invisible-yet-quite-visible elements stand at the heart of the crisis that erupted on 5 June 2017 between Saudi Arabia – joined by the United Arab Emirates and other Arab states – and Qatar. The tension had been building up in recent years with Qatar often criticized by its neighbors, and indeed a rehearsal of sorts took place in 2014 with Saudi Arabia and the other GCC countries suspending diplomatic ties with Qatar from March to December of that year, until a fragile reconciliation misleadingly closed that first episode.

Yet it is not so much the much-debated alleged policy independence by Qatar irking its neighbors or the accusations of terrorism support (in the current international context, that problematic term is now more than ever a use-it-as-you-see-fit malleable accusation) or indeed leaked emails in Washington that hold the key to making sense of the crisis but rather a combination of three eminently local recent developments having to do with Saudi Arabia’s change of leadership, Qatar’s emiral transition and the US’ new administration erratic foreign policy.

Firstly, Saudi Arabia is the ultimate survivor and a regional power never to be underestimated. This is not merely an issue of financial might – not to be discounted to be certain – but rather related demonstrably to the cumulative weight of history. The Saudis have survived Nasser, the Shah, the Gulf War, 9/11, the Arab Spring and ISIS. Their decades-long acumen was tested (and they were particularly unnerved) by the Obama administration éloignement policy towards them, particularly as it was combined with a US rapprochement with their Iranian arch-enemy. Saudi Arabia, however, is experiencing the most important leadership change since the death of the House’s founder, Abdelaziz Ibn Saud, in 1953. The arrival in 2015 of a new, more assertive king, Salman Bin Abdulaziz, and, more importantly, the subsequent, power-move appointment of his son, Mohammad Bin Salman, as crown prince is taking the country into an unprecedented lineal phase where the previous horizontal balance between the sons of Ibn Sau6d is being replaced by a new Salman dynasty-in-the-making.

Combined with the assertiveness and risk-taking that King Salman has shown in going to war in Yemen, this mutating scene explains why Riyadh increasingly harbored little tolerance for the dissonance Doha was bringing into its symphony gearing up. The June 5 break was therefore a combination of a Saudi desire to flex muscles at a key moment in the history of the new leadership, (re)establishing its dominion fully, bring order in GCC ranks under its leadership, but also the opening salvo of a new, younger and less introspective Saudi Arabia.

Secondly, Qatar has alienated too many parties. The current crisis took Doha by surprise and indeed shock. It should not have. As the small emirate launched its globally-oriented project in the mid-2000s, it had already ruffled quite some feathers throughout the region when it had launched Al Jazeera in 1997. For all the current criticism of its ambiguity and lack of coverage of the Bahrain uprising in the same manner as it did other revolts, it is worth remembering that the news channel was, however, importantly a welcome breath of fresh air in an Arab world saturated by information censorship and self-censorship. Qatar then turned that first regional revolution into a much-more ambitious plan to brand its country globally, and that is when things become complicated. What we are observing now is a political market correction-like phenomenon whereby – above and beyond the noted Saudi dimension and the engagement with Iran – all those that had invested in Qatar and failed to see returns and follow up on the part of the increasingly all-over-the-place Qataris are now considering that comeuppance as long coming, and in their view warranted. In addition, upon replacing his father in 2013, the new emir of Qatar lacked the gravitas of his father, the deposed Hamad bin Khalifa al Thani. In large ways, the current crisis also boils down ultimately to a generational issue and the personal enmity and contest now playing out between Saudi Arabia’s fast-rising 31-year-old Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (supported by the United Arab Emirates’ Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan) vs. 37-year old Qatari Emir Tamim bin Hamid al Thani.

Finally, and as also witnessed during President Donald Trump’s visit to Europe, the United States has become a force for instability for its own allies. It is no surprise that the crisis between Saudi Arabia and Qatar erupted two weeks after the visit by the US president. For the Saudis, the timing was what it was all about. As they basked in their lavish welcoming of President Trump – at the occasion of his first presidential trip abroad too – closing the sequence on the aggravating Obama years and planting this reactivating of their alliance with Washington in the face of Tehran, the last thing the Saudis could tolerate was a member of their regional brethren raining on their parade. Instead, however, of attempting to bring the tension down between Riyadh and Doha, defusing the crisis or indeed brokering a mediation between two of its key allies, President Trump chose sides and inflamed the crisis. In effect going along the most powerful of the two countries – while nonetheless simultaneously indirectly accusing Qatar of terrorism and selling it weapons within days – the Trump administration confirmed a pattern rising whereby the naked pursuit of its immediate interest is done at the explicit expense of any other considerations.

Qatar gambled but so did Saudi Arabia. And as is the US under Donald Trump doing. All three can end up losing.

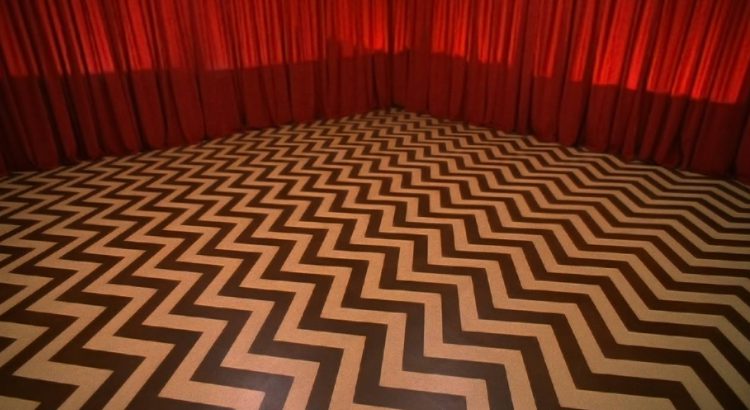

Photo: The Red Room, Twin Peaks, © ABC, 1990.