When on the evening of May 7, 2017, Marine Le Pen will be elected as president of France that country will have fully stepped into a new phase of its history and of its relationship with the Arab and Muslim world. The nature of the foreign policy which France will adopt vis-à-vis the Middle East and North Africa will not be immediately recognizable and indeed, what the government which President Le Pen will have set up would actually want from the region may not be clear readily.

Besides demands of ‘solid’ security partnerships and expectations of ‘active’ cooperation on immigration control, the relationship will move into uncharted waters. In effect and for all the Front National’s years of preparation for this moment and the explicit nature of the nationalistic foreign policies they have been gathering steam for, the main agenda, even as it relates to what they consider unshakably foreigners-in-their-midst, will be dictated by the primacy of the local.

Guidance, as it were, will be available but it will be derivative and recent. For if, arguably the British ‘elected’ Trump by making the inconceivable Brexitly possible, the former host of The Apprentice will have similarly ‘elected’ the daughter of Jean-Marie Le Pen. Populism and authoritarianism travel well under globalization. And so, explicitly modeling herself on the electoral success of the forty-fifth US President and sharing ideological affinities, Mrs. Le Pen would logically find inspiration in the policies he has adopted towards the Middle East.

Alignment with Russian President Vladimir Putin, support to Syrian dictator Bashar al Assad, criminalization of migration from the southern flank of the Mediterranean, passive animosity towards the Gulf monarchies (until a solution is found to their problematic wealth), protection of Christian minorities in the Middle East, possibly a customized Muslim Ban of her own, and generally preference for those ‘tough’ regimes instead of the democratizing wishy-washiness of that ‘Arab Spring’ which only produced the bad hombres of the Islamist winter.

The ride can be expected to be easy. Just as they did when Putin took charge of the Levant and Trump barred their citizens and/or fellow co-religionists from travel, Arab governments will display their time-tested passivity and soon enough proclaim the good relations they seek with President Le Pen in the name of international security and stability — that is, their political longevity.

France, however, is not the United States. It lacks that country’s ability to question itself and bring down presidents if they misbehave. It has a colonial past when the US Empire has none. And it harbors Europe’s largest Muslim population – as well as Europe’s largest Jewish population – Frenchmen and women who will find themselves overnight, more so than they do already since Charlie Hebdo and since Friday the 13th, and more so than Muslim-Americans do since The Ban, the enemy within.

The ‘enemy within’ to be pursued partout, a theme painfully familiar and not so long ago too in the land of fraternité – not the home of the brave.

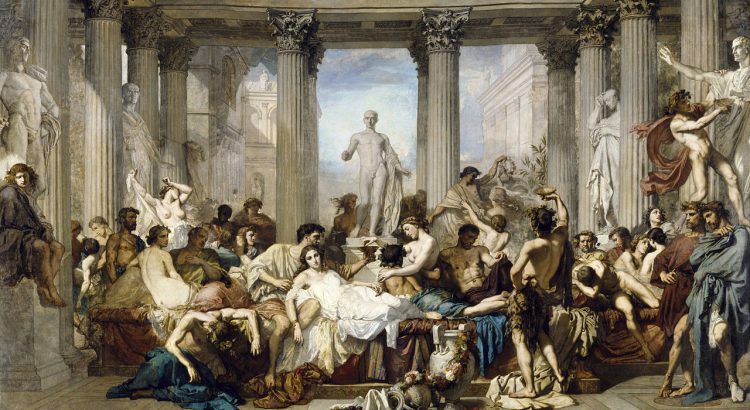

And so, in effect, a democratically-decadent France will step into the unknown not so much domestically – it has been there – but in relation to that group of states it has such strong feelings and historical bonds with. How will that relationship play overtime in a context where, as Plato noted, power would obliterate reason? Indeed what type of longer-term course correction will this generate in France once Le Pen’s presidency fails? More importantly, what imprint will it leave then and in the future on the handling of unresolved crises affecting that Arab world seen time and again only though the frame of fear and hatred.

Illustration: Thomas Couture, “Romans during the Decadence”, 1847.