Well, there I was—happily home from a place where supermarkets have not yet been invented—and I was buying one of everything.

My shopping bags were filled with delicious Swiss specialities that I had been missing—soft squishy buns, cervelas, tubes of Cenovis, mustard and mayonnaise. There were delicious fera rissoles, just-ripe avocados, and fresh herbs sprouting perkily from little pots.

I had my store card and my scanner and merrily fought (and won) a mental culinary battle back to the normality of self-selective eating.

There were no smoked pig lungs, no canned crickets, no sheep heads, no 100-year-old eggs. It was glorious.

My bags full of inventive, delicious, unrelated items – I was too freshly home to think in terms of actual meals – I was humming to myself and inserting my card into the check-out machine when an orange-bloused lady hauled me off for a “random check”.

Food reveries turned to mental compost. Guilt and fear bloomed like the blue on the Roquefort cheese chunk. Had I remembered to scan that bottle of truffle oil? Or that huge bag of dried morels?

Anxiety and blood-pressure mounted as the two employees chatted happily and rescanned my now-dangerous almost-possessions. Was I about to become one of those poor innocent people forever banned from Swiss supermarkets?

No. I passed with flying colours (I had scanned the oil bottle twice), and strode haughtily off with my treasures and retail freedom righteously intact.

That was when I discovered that I had the wrong caddy. The franc deposit was no longer in the slot. They had pulled the old bait-and-switch.

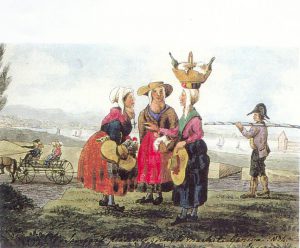

Back up to the check-out arena, I found the employee suspects and explained the loss of my franc-primed trolley. They didn’t have it, and told me calmly (condescendingly?) what had happened: I had been robbed by “gypsies”. (In the Vallée du Giffre we call them “Bohemians” which seems much more dashing.)

Back up to the check-out arena, I found the employee suspects and explained the loss of my franc-primed trolley. They didn’t have it, and told me calmly (condescendingly?) what had happened: I had been robbed by “gypsies”. (In the Vallée du Giffre we call them “Bohemians” which seems much more dashing.)

Apparently, at crowded times they come to the supermarkets and, being gypsies, are attracted by gold. Well, silver in this case. And while a person is pondering (possibly with eyes closed) whether to choose the lemon or strawberry tarts they place your bags of scanned, packed groceries into a moneyless trolley and make a speedy get-away with the cash.

I don’t know if any forensic connection has been made between the theft of my franc and the Big Maple Leaf coin robbery, but they bear curious similarities. The Berlin robbers took the 100-kg pure gold Canadian coin (53 cm diameter and 3 cm thick and worth about $4,000,000) from a museum showcase last month. They used a sledgehammer, then put the coin into a wheelbarrow to make their get-away.

This is obviously a serial-robbery situation. A copy-cat crime is also a possibility. In any case, the point of the matter is, you cannot lend anything to anybody. You take your eyes off it for one second and it’s gone.