My bones grew strong on Canadian Cheddar cheese. Growing up in southern Ontario, I don’t recall there being any other kind. Sure, there was Cheez Whiz – a fluorescent-orange goo in a jar, and even new-fangled rubbery processed cheese plastic slices for delicious grilled cheese sandwiches in the electric frying pan; but for “real” cheese, Cheddar was it. One winter, a rather large lump, about the size and shape of a shoe-box, somehow made its way into the house. It was kept down the basement with the mice and only addressed in cases of extreme hunger. I recall it fondly.

Here in the Geneva countryside these days, the cheese drawer in the kitchen fridge is importantly filled with Gruyère, Emmental, Roquefort, and La Vache qui Rit. A Reblochon, Tête de Moine or a Mont d’Or also make cameo appearances from time to time. Any Cheddar placed in there is not touched by common human hands. Cheddar is venerated as part of the kitchen covenant and is uniquely reserved for a weekly lunch-time ritual shared with addicted grandchildren.

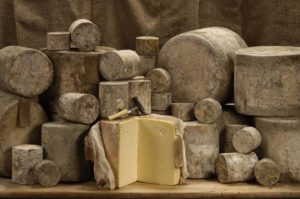

Proper English Cheddar cheese has to be made within a 30-mile radius of Wells Cathedral in Somerset in the south-west of England; and the nec-plus-ultra version should sit for many months in the damp dark caves of the Cheddar Gorge. The heavy yellow square I buy every week even has a picture of a church on the front of the package and is called Cathedral City Cheddar, which, without a doubt, proves its total authenticity.

Now, my Tuesday luncheon special is deceptively known simply as “Macaroni and Cheese”. This is not your boxed processed dinner, or your flour and water version of dried-out common-style dish of the same name. This is more like the splendid centrepiece described in Guiseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard which was served cold at a summertime banquet at the crumbling old Palermo palace in Sicily.

Now, my Tuesday luncheon special is deceptively known simply as “Macaroni and Cheese”. This is not your boxed processed dinner, or your flour and water version of dried-out common-style dish of the same name. This is more like the splendid centrepiece described in Guiseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard which was served cold at a summertime banquet at the crumbling old Palermo palace in Sicily.

My macaroni and cheese is equally magnificent. The whole huge hunk of Cheddar is grated on an old-fashioned circular grater with a turning handle and three little legs. It is then folded lovingly into the steamy creamy béchamel sauce. It is rich and unctuous. It is then gently mixed into Swiss Alpine macaroni, sprinkled with parmesan and baked to a golden brown. People fall silent as they eat. It is my sure currency of pure love.

So, with an uncertain future and Brexit looming, stockpiling has started. I already have two fat slabs of pure Cheddar hidden away and I plan to unobtrusively get many many more. Unopened, the due date gets me nine months into the future, so there is no panic at the moment, and, if anything, my mature cheddar will simply get even more mature.

So, Britain, do cheer up! With me, your present and future Cheddar cheese sales are assured. (You, though, might think about stocking up on macaroni des Alpes … Just sayin’.)